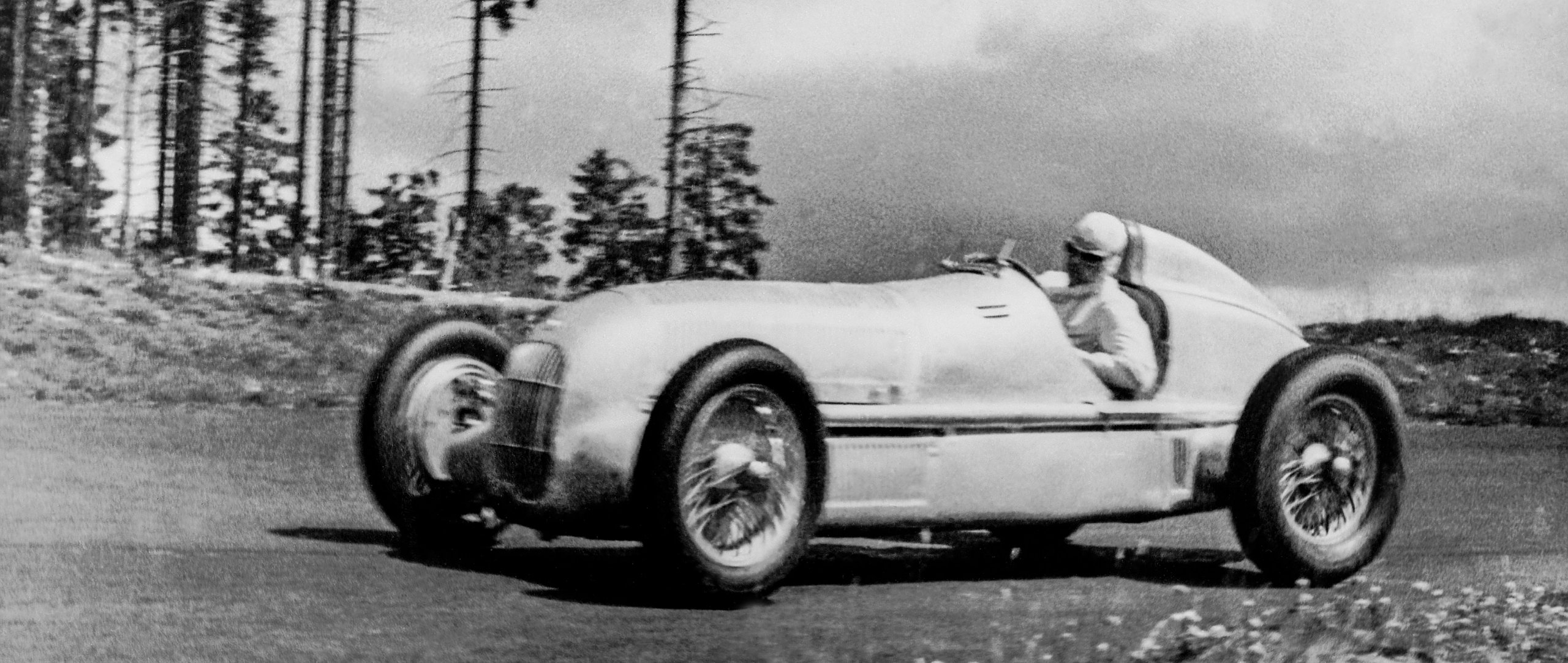

Die Silberpfeile – The Silver Arrows Teams

The Fuhrer has spoken. The 1934 Grand Prix formula shall and must be a measuring stick for German knowledge and German ability. So one thing leads to the other: first the Fuhrer’s overpowering energy, then the formula, a great international problem to which Europe’s best devote themselves, and finally, action in the design and construction of new racing cars.

Mannschaft und Meisterschaft

Mercedes-Benz

In response to the Stock Market crash of 1929 and the resulting downturn in the World’s economy. Mercedes was forced to temporarily stop their racing program. Their team manager, Alfred Neubauer lived for racing and the idea of being re-assigned to some factory or even worse desk job held no appeal for him. When directing the racing team, Neubauer’s word was law, now he would be just another worker among the masses but the new Auto Union team had approached him with a invitation to join them. Could he really leave Mercedes after all these years. Auto Union promised to embark on a future racing program but the future of Mercedes, at least when it came to racing was at best uncertain. Neubauer met with the managing director of Auto Union, Klaus von Oertzen. That night Neubauer wrote a letter of resignation to Daimler-Benz.

Twenty-four hours later Dr. Kissel, our Managing Director, asked me to go and see him. He came towards me as soon as I opened the door of his office, an anxious look on his face. ‘My dear Neubauer,’ he said, almost pushing me into a vast leather armchair.

‘What in heaven’s name has come over you? You’re not seriously thinking of leaving us.’

‘I’m afraid so,’ I muttered.

‘But why? What’s the matter?’

My eyes wandered for a moment to the picture that hung behind Kissel’s desk. It was a portrait not of President von Hindenburg or of Kaiser Wilhelm but of Rudi Caracciola. ‘It’s racing that’s the matter,’ I said. ‘I’m only half-alive without it, an office desk doesn’t suit me.’

Dr. Kissel gave me a long, earnest look. ‘You shall have your racing,’ he said solemnly. ‘I promise you that, while I have any say here, we’ll be building racing-cars again, as soon as it’s economically possible.’ My heart lifted. Then I realized with a shock of alarm that I had already signed a provisional contract with the Auto-Union.

‘Let me see it,’ said Kissel.

He read through it quickly. When he saw the salary they were offering me he raised his eyebrows. Then he folded the document carefully. ‘Please leave this with me,’ he said. ‘I’ll arrange it somehow. As for your salary, you can earn as much with us as the Auto-Union have offered-and a bit more. As from today.’ I was lucky. I could at least afford to wait till motor racing became economically possible’ again.

(Speed was my Life by Alfred Neubauer)

Initially the overall responsibility for Mercedes’ racing efforts was held by Dr Hans Nibel but after his untimely death from a stroke in November 1934 that duty was assumed by Max Sailer. During their peak years of 1937-38 the team was divided into three main departments, headed by Fritz Nallinger who was in charge of Design, Rudolf Uhlenhaut of Construction and Preparation and Alfred Neubauer of the Racing Department. The Design department was sub-divided into two main sections, Engines under Albert Heess and Chassis under Max Wagner (who ironically, while at Benz, was involved in the design of the famous rear engined Tropfenwagen).

The car would then be moved to a sound -proofed enclosure and placed on a wheeled dynamometer and driven for hours on end at different speeds while facing a large fan which helped to adjust room temperature along the regular room controls. Various loads were applied to the car and all of the gears were utilized in order to best reproduce race conditions.

Once at the track the came under the control of Neubauer and his famous flags. Much was made of the German teams precision and a large part of it can be directly attributed to Neubauer as even his rivals at Auto Union were forced to admit. Neubauer was a natural born organizer and all details were noted on paper, and instructions regarding work on the cars were written and passed on to the mechanics. As mentioned earlier the race weekend was used for driver practice.

At just the precise time Neubauer would signal the start of practice and the mechanics would engage the electric starter, and the engine would burst into life. After another signal the car would be driven for a few laps at moderate speeds and then coast back into the pits. As soon as the car stopped the mechanics would descend on the car and check the plugs in order to adjust the proper fuel mixture. If the plugs were sooty the mixture was over-rich and need to be weakened by changing the carburetor jets. If the plugs looked dry and burnt then the mixture need richening. Taking into consideration the practice performance by his drivers as well as that of the opposition, Neubauer would decide on race tactics.

Meeting with his drivers the evening before the race the battle plan, for there could be no other word for it, was laid out. Some times the drivers would quietly agree to the tactics but other times the drivers would argue long and hard over perceived slights. Neubauer’s orders were though always followed, almost. Just as critical as his pre-race tactics were it may have been his ability to adjust them as the race proceeded that would prove to be his greatest skill. Pitstops were also practiced and the Mercedes team was renowned for their quick and precise work. But more than just a stickler for details and practice, Neubauer was a leader of men who was held in a mixture of awe and affection by all who worked for him.

With this flawless organization and a strong driver line-up would Mercedes go into battle and the legend of the Silver Arrows was born.

Auto Union

750-Kilo Formula. 16-Cylinder Auto-Union Racing Engine

| Year | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 |

| Cubic Capacity (cc) | 4,360 | 4,950 | 6,010 | 6,330 |

| Stroke x Bore (mm) | 75 x 68 | 75 x 72.5 | 85 x 75 | 85 x 77 |

| Supercharger Boost (atmospheres) | 0.6 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Compression Ratio | 7.0:1 | 8.95:1 | 9.2:1 | 9.2:1 |

| Output (bhp) | 295 | 375 | 520 | 545 |

| At RPM | 4,500 | 4,800 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| Torque (lb/ft) | 380 | 477 | 627 | 650 |

| Output per Liter (bhp/liter) | 67.5 | 76 | 86.5 | 86 |

| Piston Speed (ft/min) | 2,226 | 2,364 | 2,777 | 2,777 |

In November of 1933 the first car broke cover on local roads just outside the factory gates before being taken to the Nurburgring where Willy Walb, the first team manager, drove it. The following March it was taken to Avus, the high speed circuit near Berlin. Hans Stuck was the driver this time and promptly set three new World Records.

The first major race under the new formula for the German cars was the Avus GP in May. Both Mercedes and Auto Union were there along with the usual assortment of Bugattis, Maseratis and of course Alfa Romeos. After suffering some mechanical problems during practice the Mercedes team cars were withdrawn, after the race the Auto Union team may have wished to had done the same. There were three Auto Unions for Prince zu Leiningen, August Momberger and Hans Stuck. Stuck surged into the lead at the start of the race and after the first lap he had a one-minute lead over Louis Chiron. It was as if he was in a race by himself but after lap 12 he was out with clutch failure. The Alfas of Guy Moll and Achille Varzi beat the Auto Union of Momberger over the line but notice had been served. The next race was the Eifel GP at the Nurburgring and the German cars tasted first blood with the Mercedes of von Brauchitsch leading the Auto Union of Hans Stuck. The most important race of the calendar was still the French Grand Prix, but the race turned into a disaster for both Mercedes and Auto Union when all of the German cars retired. The German GP was next and with it came the first victory for Auto Union when Hans Stuck beat the Mercedes of Luigi Fagioli.

Professor Porsche attended almost every race of the first season and would study the race reports and film taken of his cars. Professor Eberan-Eberhorst helped develop a special on-board recording instrument that plotted various parameters such as car speed, engine speed, shifting and breaking points.

After a rough start the year finished quite well for Auto Union and Hans Stuck with victories in Switzerland and Czechoslovakia in addition to the aforementioned German GP. With Han Stuck at the wheel they also won several hillclimbs including Schauinsland, Kesselberg, Feldberg and Mont Ventoux. Against the Mercedes driver line-up of Caracciola, Fagioli and von Brauchitsch Auto Union only had Stuck with remotely comparable experience.

Auto Union was also heavily involved with speed attempts producing several special models with enclosed streamlined bodies. In 1934 Stuck achieved seven World records in the 3 – 5 liter class. The team utilized extensive testing in the wind tunnel at the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt in Berlin even employing side skirts to improve aerodynamic downdraft.

The Auto Union originally used the chassis tubes as water carriers but due to chassis flexing water was leaking from tiny cracks in the welds. After attempts to fix the problem were made by way of additional bracing and different tube profiles the practice was abandoned.

For 1935 Hans Stuck was joined by the great Italian driver Achille Varzi. Later that year they were joined by Bernd Rosemeyer. The year saw more success for the team from Zwickau. Stuck won in Monza in addition to two hillclimbs while Varzi was victorious in Tunis. But Mercedes led the way and the inaugural European Championship went to Rudolf Caracciola. A modification was made to the car, which would have profound impact the following year. Ferry Porsche; the Professor’s son and a talented engineer in his own right discovered that when accelerating out of a corner the inside rear wheel would spin furiously. Having also experienced a similar problem with their road cars they had ZF in Stuttgart build a new limited-slip differential for their racecars. This modification and the brilliance of their new star Rosemeyer resulted in Auto Union’s greatest season. Rosemeyer would also claim the European championship for his own that year. Auto Union’s domination was so great that Mercedes actually pulled out of the last few races in order to overhaul their entire organization. Arrayed against Rosemeyer for 1937 was a Mercedes team of Caracciola, von Brauchitsch, Lang and Dick Seaman.

While Mercedes had more total victories than Auto Union the latter team raced with a budget only half the size of the former. Ferry Porsche would later comment that as far as he was concerned Mercedes’ one clear advantage was their team manager, Alfred Neubauer. That while Auto Union was ably served by Willy Walb and later Dr Karl Feuereissen there was only one Don Alfredo! You could easily add Rudolf Uhlenhaut to the list as a distinct advantage for Mercedes. Not only a brilliant development engineer he could also drive the cars at racing speeds. Mercedes also had two groups of drivers those that were what he called the gentleman drivers like Caracciola and von Brauchitsch and the ones that graduated from their mechanics like Lang while at Auto Union none of their mechanics became racing drivers. On an ironic note while Auto Union became famous for their rear-engined racing cars they never produced a production car with the same layout.