Mercedes W 25

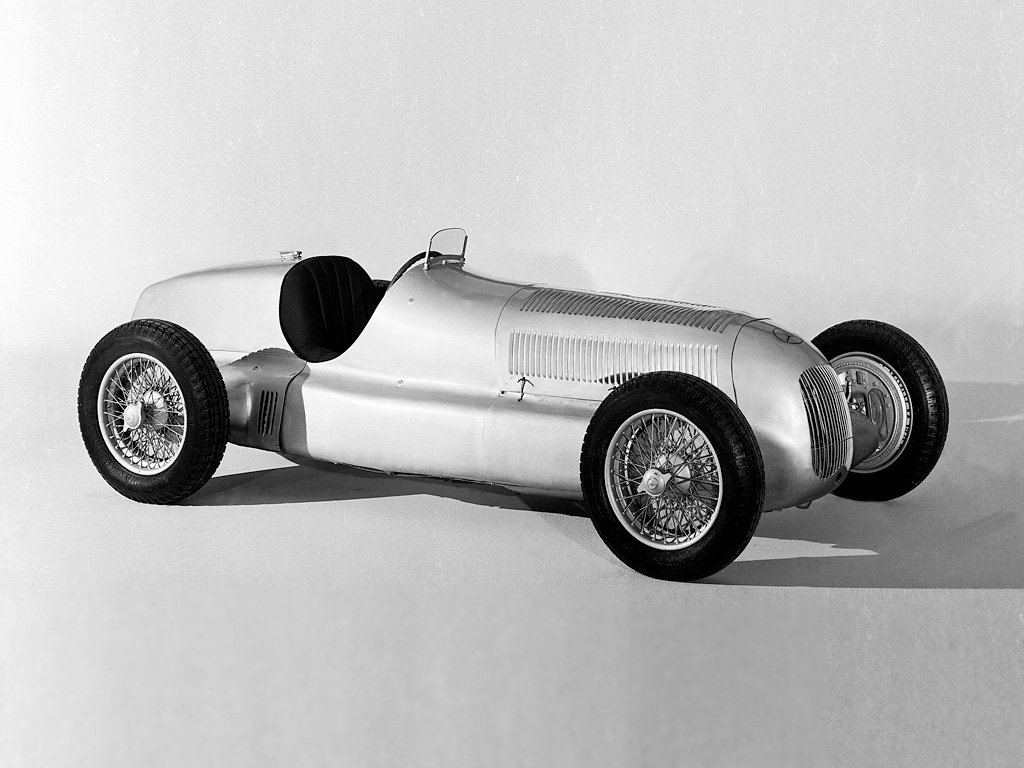

Car: Mercedes W25 / Engine: 8-Cylinder In-line / Maker: Daimler-Benz / Bore X Stroke: 78 mm X 80 mm / Year: 1934 / Capacity: 3,360 cc / Class: Grand Prix / Power: 354 bhp at 5,800 rpm / Wheelbase: 107.2 inches / Track: 58.0 inches front, 56.0 inches rear

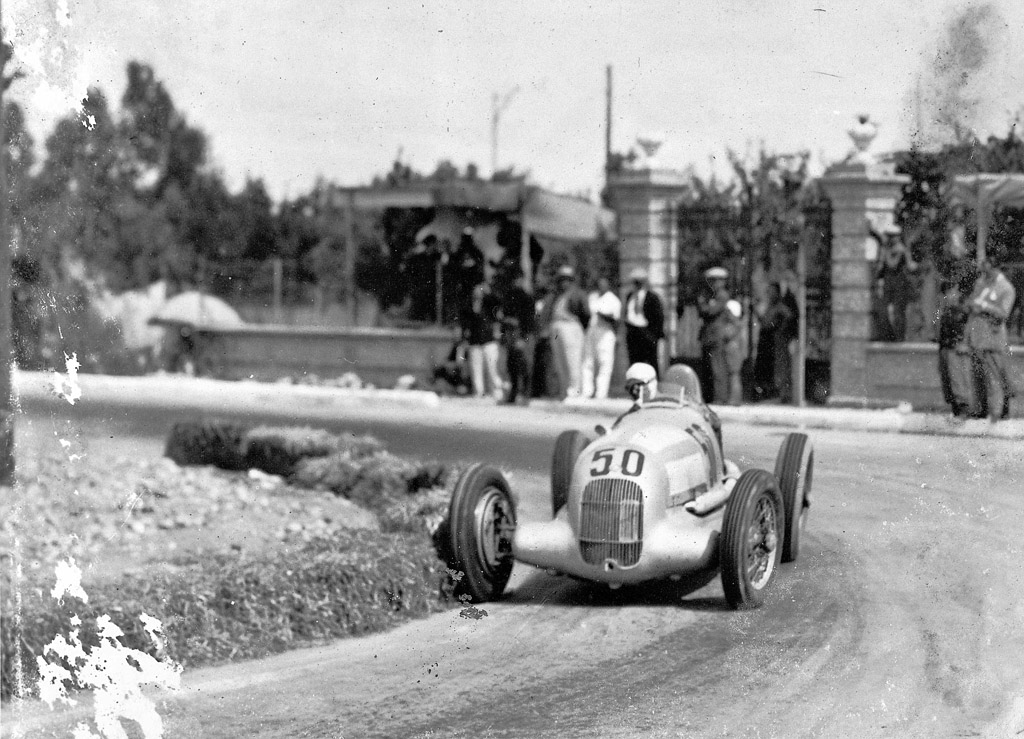

The new Auto Union, designated the P-Wagen, was ready in late fall, 1933, several months before the Mercedes.In January they invited the press to view their new car and the press in their enthusiasm declared the sleek new car as the German race car. Daimler-Benz who had yet to debut their car was not amused by this new upstart. 1934 would bring in the 750 kilogram formula that was meant to make racing cheaper in the cash strapped Thirties. The minimum race length was set at 500 kilometers.

With the rise of the National Socialists steps were taken to expand the economy. Credit was more freely given, armament production was of course increased and labour unions, the traditional strength behind the leftist parties were banned. Daimler-Benz, in the person of Jacob Werlin had a personal acquaintance with the new German Chancellor, Adolf Hitler. With his help the Transport Ministry would pay 450,000 Reichsmarks to the firm that produced a Grand Car with bonus payments of 20,000, 10,000 and 5,000 for finishes 1st through 3rd. Unfortunately for Daimler-Benz the party was crashed by Auto Union and the stipend would have to be shared by the two firms. Historically this was a third of the budget that Wilhelm Kissel had estimated and only 10% of what was actually spent each year.

Finally the new car designated the Mercedes W25 was ready. Produced under the technical direction of Dr Hans Niebel with Max Wagner as head of chassis design, Albert Heess and Otto Schilling in charge of engine development and Fritz Nallinger’s experimental department overseeing the building and testing of the actual race cars. Rudolf Caracciola, who had raced an Alfa Romeo in 1932 sold his 1933 car that had crashed at Monaco the next year to Daimler.This would prove quite an advantage as a measuring stick for the new W25. After some discussion they decided that unlike Auto Union they would adopt a front engined layout. Power was provided by a twin ohc supercharged straight eight. The suspension was all-independent with wishbones and coil springs at the front, swing axle and transverse quarter elliptics at the rear. Stopping power was provided by hydraulically assisted drum brakes. Initially the cars were painted white, the German national racing color, but according to legend the paint was later removed to save weight, exposing the silver bodywork. The press soon began calling the race cars die Silberpfeile (Silver Arrows).

The new cars won four major Grand Prix races as well as two hillclimbs during their inaugural first year. Autocar’s reporter called the screaming Mercedes, the noisiest cars on earth. Initial power ratings for the car was 314 bhp at 5,800 rpm. Using a new fuel mixture provided by Standard Oil that replaced the gasoline/benzol with methyl alcohol horsepower was bumped to 354 bhp. A new golden era of racing had begun.